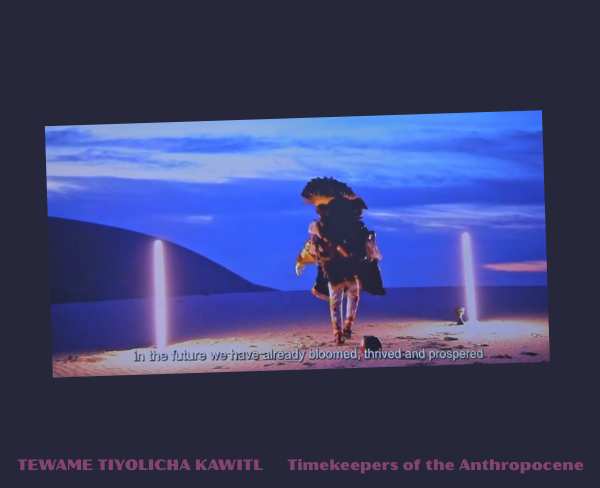

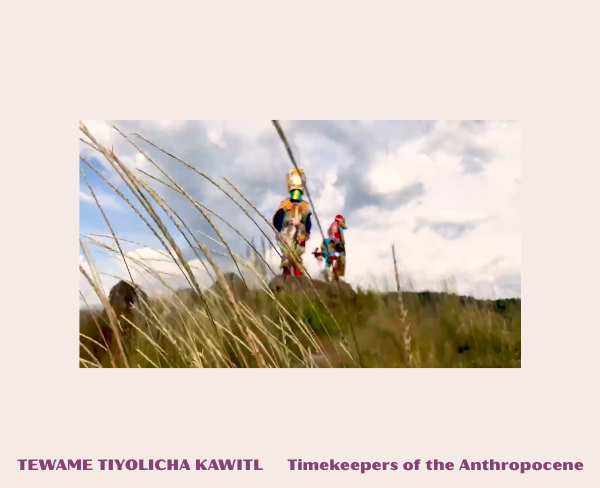

In an era where digital tools can produce infinite images at the click of a button, the real scarcity is not creativity but time—the capacity to feel its textures, to track its rhythms, to situate ourselves within larger cycles of ancestry and ecology. Tewame Tiyolicha Kawitl: Timekeepers of the Anthropocene enters this landscape as a conceptual hinge: an invitation to rethink how we hold time, and how digital art might become a vessel for repairing its ruptures.

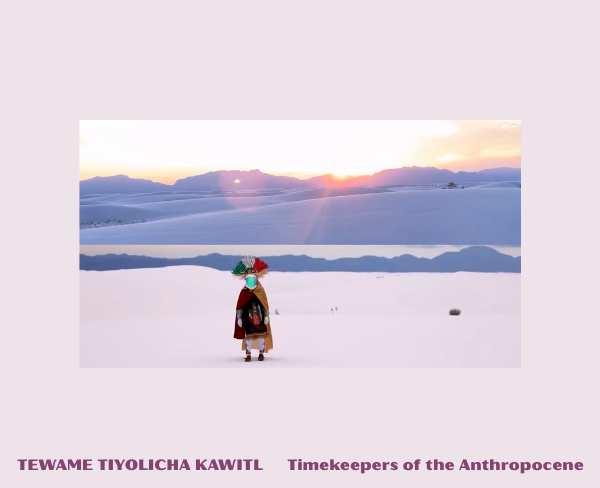

The Timekeepers remind us that time is not a neutral grid stretching infinitely forward, but a cultural technics. Long before clocks, calendars, and carbon markets, many societies tracked time through more intimate compasses: the behaviour of animals, the flightpaths of birds, the hum of seasonal winds, the rising and setting of stars against landscapes, the silent messages carried by ancestral images. These forms of timekeeping stitched human attention to ecological rhythms. They bound memory to land. They were not tools of measurement; they were instruments of relationship.

By contrast, the Anthropocene has been built on a violent temporal abstraction. The colonial and industrial eras imposed a linear, extractive temporality—one that measures productivity rather than reciprocity, acceleration rather than attunement. It is this regime of time, not simply “the human species,” that has destabilised the planet’s climate and our collective nervous system. The Timekeepers project intervenes by reactivating ancestral calendars and cosmological clocks: not as artefacts of nostalgia but as technologies of ecological responsibility.

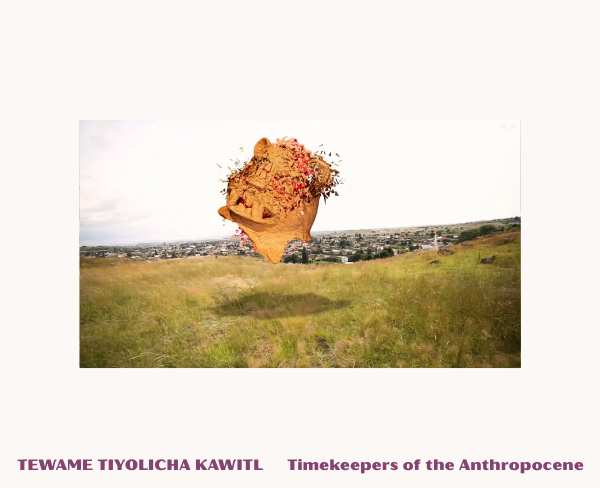

Placed in conversation with digital art, this reorientation becomes urgent. We often imagine AI and digital tools as engines of speed, generating aesthetics at a scale and velocity that dwarfs human intuition. Yet digital art—if approached with care—can instead become a temporal prosthesis: a way to render complex cycles, to visualise forgotten kinships, to slow images down until they speak again. Rather than replace human imagination, these tools can extend its reach into dimensions of memory and relation that contemporary life has eroded.

To work digitally in the spirit of the Timekeepers is to treat the act of rendering not as production but as ritual calibration. Every prototype becomes a moment of attunement. Every iteration is a return to the question: What time is this image keeping? Is it aligned with the pulse of the land or the logic of the extractive grid? Does it accelerate the world, or does it help us feel the world more slowly?

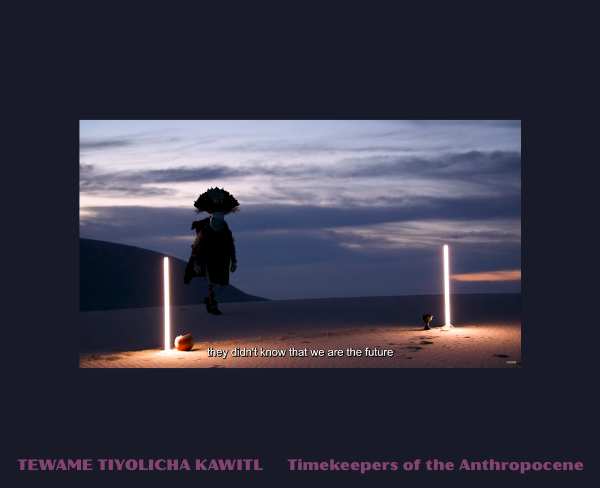

In this sense, digital art becomes a custodial practice—not future-facing in the speculative sense, but future-caring in the ecological sense. It asks us to hold multiple temporalities at once: the ancestral past, the wounded present, the uncertain future. The Timekeepers teach that art must be accountable to these layers. Images do not merely describe the world; they orient it. They are compasses for perception.

Digital artists working within this framework emerge as stewards of attention. Their task is to reopen the time-signatures of old worlds. They listen to the texture of seasons, the silence between stories, the memories encoded in ritual objects, and let these rhythms inform how an image unfolds. Technology becomes a collaborator in cultural repair—a means of restoring relational imagination where it has been thinned by speed and abstraction.

Ultimately, Tewame Tiyolicha Kawitl offers a counter-Anthropocene vision: not a world rescued by technological mastery but a world rebalanced by temporal humility. If we accept that the climate crisis is also a crisis of time—of lost alignment, of broken clocks, of futures colonised by the metric of profit—then digital art becomes one of the unexpected mediums through which we might learn to keep time differently.

The Timekeepers ask us to imagine digital tools that do not overwhelm us with infinite possibilities but guide us back to the finitude that makes life meaningful: the cycle of seasons, the lifespan of a tree, the memory of ancestors, the slow intelligence of land. They ask us to treat each rendered image as a small act of calibration in a world that has forgotten how to count what truly matters.

In their company, digital art can become a new grammar of ancestral time—an instrument for repairing the broken clocks of the Anthropocene and for reweaving ourselves back into the living calendars that once held us.