The Crisis of Crises

A mural peels off a forgotten wall in Johannesburg—a child with a gas mask staring at a burning sky. It could be Banksy or any one of the thousands of young artists transmuting their fears into art. These visceral images have become the emotional wallpaper of our time. But what happens when awareness becomes overwhelm? When education mutates into indoctrination? And when the climate crisis is just one part of a broader narrative of collapse that we now call the “Polycrisis”?

Art Stoke Commons, still in its incubation phase, was born from a need to hold these types of contradictions and stories differently—not to escape them, but to express and reframe them. This article explores the difference between climate education and climate indoctrination, the impact of fear-based messaging on the youth, and why understanding the climate crisis through the lens of polycrisis might lead us to more empowering cultural responses.

Definitions and Distinctions

The Climate Change Narrative

At its core, this narrative centers on greenhouse gases, carbon footprints, and the need for urgent environmental reform. Framed through the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports and widely circulated media imagery, it often zooms in on rising temperatures, melting ice caps, and the individual responsibility to “go green.”

But this narrative has increasingly been hijacked by corporate agendas, political lobbying, and even media fatigue—where repeated alarmism can overwhelm and cause apathy or avoidance. Climate change becomes a buzzword, and public action is channelled into consumerism: buy a hybrid car, recycle more, fly less. This oversimplification can breed cynicism or eco-fatigue, especially in youth who sense the deeper structural issues being ignored.

The Polycrisis Narrative

Coined by historian Adam Tooze and increasingly referenced in global institutions, the polycrisis narrative acknowledges that multiple interconnected crises are colliding: ecological collapse, inequality, inflation, digital surveillance, authoritarianism, and mental health decline. Climate change is one actor in an ensemble cast of systemic failures.

This narrative does not offer easy villains or simple solutions. But it may better equip us to approach climate change not just as a scientific emergency, but as a cultural, psychological, and systemic reckoning.

Climate Education versus Indoctrination

Climate Education

True climate education invites curiosity, interdisciplinary thinking and local action. It recognizes the complexity of the crisis and encourages young people to explore deeper historical forces—capitalism, colonialism, industrialization—alongside power dynamics (who pollutes vs. who suffers) and intersectional impacts (race, ethnicity, gender, class).

This kind of education fosters resilience, community engagement, and creative problem-solving. It tells the truth—but it also makes space for imagination.

Climate Indoctrination

Climate indoctrination, on the other hand, narrows the frame. It often uses repetitive crisis messaging, overemphasizes apocalyptic imagery, and moralizes personal behavior. Instead of systems thinking, it induces shame, overwhelm or paralysis.

Media, education systems, and even some activism channels unintentionally perpetuate this by leaning too heavily on fear without pathways for agency. Young people are left with overwhelming urgency but no compass to navigate multiple, often contradictory priorities.

The Rise of Climate Angst in the Global Youth

Surveys show a marked rise in climate-related anxiety, particularly among the under-25s. A 2021 Lancet study of 10,000 young people across 10 countries found that 59% were “very” or “extremely” worried about climate change. Over 45% said these fears negatively impacted their daily functioning, and 75% agreed that the future is frightening. Many respondents also reported feeling betrayed or ignored by governments, with 58% stating that their governments were failing young people. These sentiments were consistent across both the Global North and Global South, though the impacts were often more acute in regions already facing social or ecological instability.

The youth are often praised for their activism, but this sometimes masks a deeper issue: they feel abandoned. Burdened with fixing a world they did not break, while watching governments and corporations perform sustainability theater.

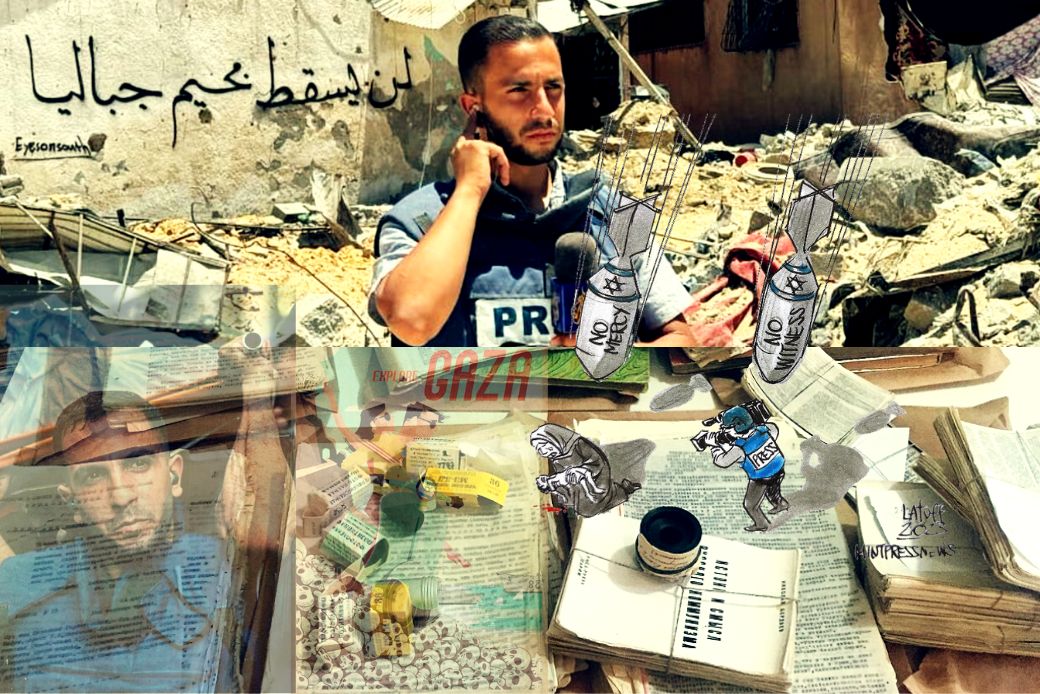

This is where cultural responses become essential. While policy lags and markets distort, art has the agility to speak truthfully and imaginatively into complexity. Through comics, murals, music, and digital storytelling, young artists are documenting not just the crisis, but their experience of it — reclaiming the narrative from the margins. These creative expressions do more than raise awareness, they reweave meaning into fractured realities. They don’t demand optimism, but they do resist erasure — the quiet dismissal of their voices, their fears, and their futures. And in doing so, they create spaces for agency, healing and solidarity — especially for those excluded from decision-making tables. Culture, then, becomes a counterforce to abandonment: a way to witness one another, to metabolize grief, and to remember that another story — one rooted in justice and interconnection — is always possible.

The Danger of Incomplete Narratives

An incomplete climate narrative—one that excludes systemic critique—risks becoming a tool of control. It shifts the blame to individuals, obscures structural violence, and depoliticizes the ecological struggle.

This is where the polycrisis lens helps. By naming the connections between extractive capitalism, colonial legacies, and climate change, we return to a more honest and potentially transformative frame. It also sharpens our awareness of narrative tactics—especially those that blend spectacle and sincerity. In this grey zone, the docutainment trap thrives: a seductive mix of entertainment, documentary, and ideological messaging that can subtly depoliticize the crisis while appearing to spotlight it.

Art as Counter-Narrative

Art Stoke Commons emerges as a space-in-formation to foster this transformation. Though still in its early stages, one objective is to nurture cultural responses to the polycrisis that are embedded in community, complexity and creativity. In practice, this could mean funding street murals that interrogate extractive systems, or publishing comics that dramatize climate justice through local mythologies. It means putting tools in the hands of artists—not just to critique, but to co-create.

What if the polycrisis isn’t just a tangle of emergencies — but also a cultural moment calling for deeper sense-making? While power struggles paralyze politics and profits divide economies, culture moves—fluid, open, and vital. It is through culture that we metabolize complexity, make meaning from chaos, and stitch together new social fabrics. Instead of a crisis of solutions, we may be facing a crisis of imagination. And in this space, cultural narratives matter—not to simplify the entanglement, but to help us live within it. This is where frameworks like Art Stoke Commons step in: not as models or blueprints, but as cultural compost heaps where new values, aesthetics and social experiments can take root.

Art doesn’t pretend to offer solutions—but it can offer sanctuary, sense-making and resistance. Through comics, murals, storytelling and digital media, artists can disrupt indoctrination and invite re-imagination.

Reclaiming Narratives in an Age of Entanglement

The climate crisis is real. But so is the crisis of how we tell the story.

Moving from a siloed climate narrative to a polycrisis perspective allows us to stop treating symptoms and start addressing roots. It replaces false urgency with deep coherence, and individual guilt with collective strategy.

We need education that empowers, not indoctrinates. Stories that hold both grief and possibility. Cultural spaces that centre interconnection, emergence, and meaning-making. Art Stoke Commons aims to be one such space — a commons for storytellers, artists, and youth to resist fragmentation and shape new narratives for a world in flux.

The question is no longer just how to solve climate change. It is how to live meaningfully within entangled realities — how to transform the polycrisis from a web of disempowerment into a wellspring of deeper imagination. This isn’t a call to escape the crisis. It’s a call to shift the story — away from fragmentation toward coherence; from isolation to connection; from resignation to cultural aliveness.

[…] our previous piece, Beyond Climate Panic, we pointed to how emotional urgency can silence complexity. Here, we go deeper into this slippery […]