A Wound Reopened

I was born into apartheid South Africa. As a young adult, I witnessed the moment South Africa became free. I carried with me the hope that true healing would follow, that restorative justice would be the path to a new society. I believed, then, that we were entering an era where memory, pain, and repair would be honoured.

But over time a different reality took shape. The architecture of apartheid remained -redecorated, but still intact. Its spatial, racial, and economic logic quietly endured. What was promised as transformation too often became assimilation. What was needed – deep healing – was postponed, distorted, or denied.

Now, watching the genocide of Palestinians in Gaza by colonial apartheid Israel, that old wound has been ripped open. And here in South Africa, the overwhelmingly racialised divide in political and public support for apartheid Israel exposes how far we still are from collective healing. The echoes of apartheid are not distant – they are immediate, global, and local. And they remind us: apartheid did not die – it evolved.

For many of us, this moment has reignited a painful clarity: we have not healed. The systems may have changed on paper, but the deeper work of cultural transformation is far from complete.

This is where art matters.

This is why South African digital art needs its own space – not one shaped by international markets, foreign gaze, or Western algorithms, but one that makes room for local truths, cultural repair, and political honesty. We need a space that lets us speak to each other before we perform for the world.

The Global Digital Art Landscape and Its Limits

A handful of powerful international platforms and institutions dominate the digital art space. These platforms set the rules – economically, aesthetically, and culturally. As a result, many South African digital artists find themselves creating for a global (and often Western) market, subtly or explicitly encouraged to translate their context into something legible, consumable, or exotic for outsiders.

This has led to a homogenization of creative output. Despite the promises of digital democratization, a cultural monopoly persists, where local nuance, unresolved narratives, and complex post-apartheid and postcolonial identities are too often filtered, softened, or erased.

But for countries like South Africa, digital art cannot only be about visibility or commerce. It must also serve as a tool for collective reimagining and repair.

The Healing and Integrative Role of Digital Art in Post-Apartheid South Africa

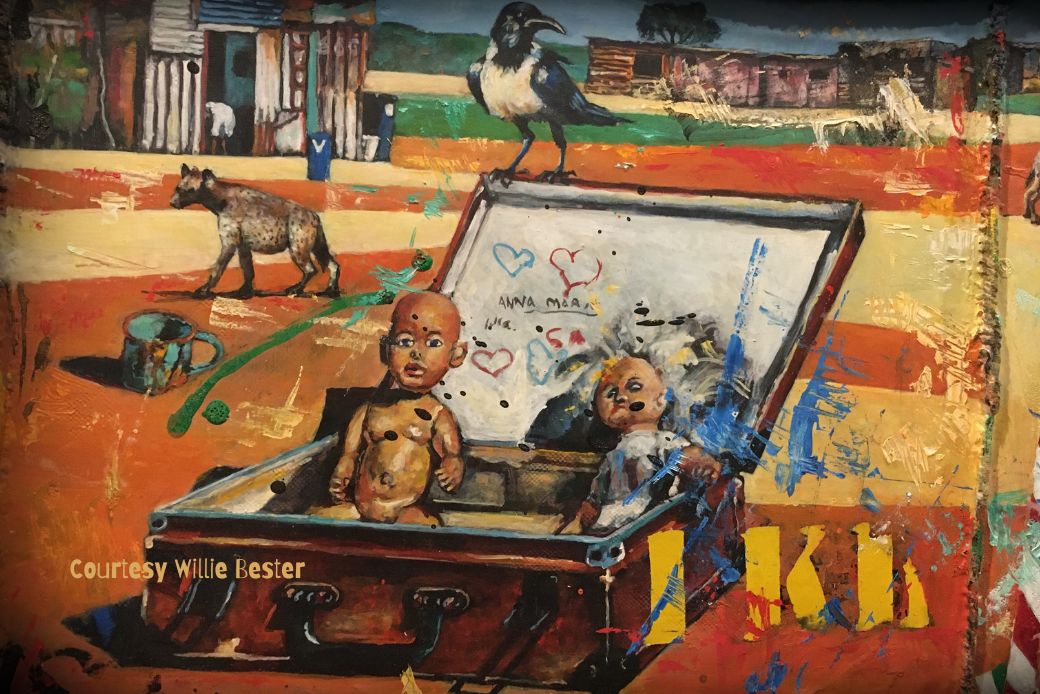

South Africa is a country still shaped by the aftershocks of apartheid: structural inequality, racialized poverty, spatial injustice, and psychological trauma. Art has long played a role in making these realities visible and in giving voice to those silenced. In the digital age, this role has not diminished – it has evolved.

Digital art has the potential to serve as a new form of cultural integration and healing

- A way for fragmented communities to reconnect,

- A space to surface suppressed histories and alternative futures,

- A canvas for re-authoring narratives shaped by resistance, survival, and renewal.

Yet, this potential is lost when South African artists are producing for external audiences that do not share the memory, the pain, or the hope that grounds their work.

In a country where the need to rewrite the past is still urgent, digital art should not be reduced to tokenized pixels. It should be part of a national cultural ecosystem that allows truth, disruption, and ordinary complexity to emerge.

This “ordinary” is often invisible to international digital art markets. But it is where the deepest cultural healing happens. And it is precisely what a decentralized South African digital art commons can support—a place where artists are not just content creators but custodians of memory and imagination.

Why Art Stoke Commons Exists

At the heart of Art Stoke Commons is a single mission:

To re-author the South African story.

This means:

- Creating a decentralized, locally owned digital infrastructure where artists can produce work that speaks to home, not to hype.

- Using blockchain not just for ownership and provenance—but for cultural accountability, shared stewardship, and local creative economies.

- Supporting art that is not only aesthetically powerful, but socially embedded, historically aware, and psychologically restorative.

In this way, Art Stoke Commons stands as a refusal—a refusal to let South African digital creativity be flattened by global platforms, and a reclamation of the right to cultural self-determination in the digital age.

[…] This is a Part II of Part 1 Slow-Profit DAOs and Cultural Infrastructure: A New Commons for Systemic Change. Consider also reading Why South African Digital Art Needs Its Own Space. […]