There is a new kind of extractive industry rising quietly across the African cultural landscape—nothing as obvious as mining, nothing as brutal as the colonial museum raid. Instead, it arrives with friendly logos, “innovation labs,” creative grants, workshops for emerging storytellers, and the promise of global visibility.

It speaks of “capacity building,” “climate storytelling,” “future literacy,” “XR for good.”

Its money comes from the usual constellation of foreign donors: EU cultural institutes, USAID, US State-funded arts programs, Silicon Valley philanthropy, and increasingly the World Economic Forum, that global clearinghouse of elite futurism. It looks soft, benign, even generous.

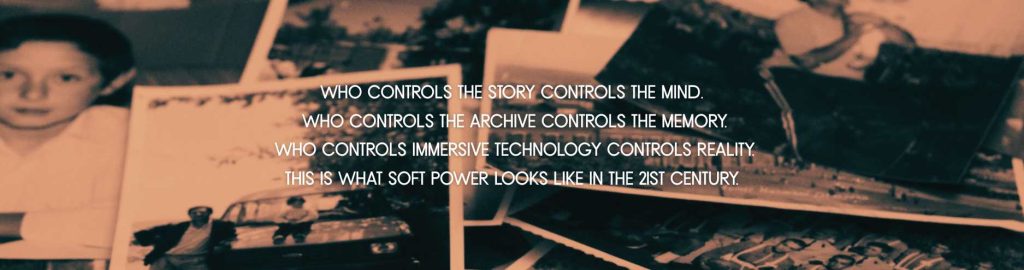

But the deeper one looks, the clearer it becomes: Immersive storytelling in Africa is becoming a frontline for soft-power geopolitics, digital extractivism, and the quiet capture of African youth imagination.

1. Dollar–Euro Philanthropy Loves South Africa for One Simple Reason: The Rand Is Cheap

Let’s start with the economics. A €100,000 / $100,000 arts grant in Berlin or New York barely covers a single senior staff salary.

In South Africa, that same money funds:

- an entire “immersive storytelling lab”,

- several artist teams,

- travel,

- equipment,

- marketing,

- festival submissions,

- and public relations.

Foreign NGOs can stretch their money across African bodies, African creative labour, African intellectual property at a fraction of the cost.

It is billed as “support.”

It is, in practice, a favorable foreign exchange arbitrage strategy: high-impact PR for low financial outlay.

This is why every few months we see another:

- climate storytelling lab,

- “archives-to-AR” program,

- speculative futures residency,

- digital arts incubator,

- VR festival with an international curator parachuted in.

And almost always, behind the scenes: European cultural diplomacy offices, North American philanthropic money, and the WEF orbit.

2. Immersive Technology as Soft Power: Training Gen Z for Someone Else’s Future

VR/AR are not just art forms.

They are strategic technologies that define:

- simulation cult(ure),

- behavioural design,

- training environments,

- attention capture,

- emotional manipulation,

- and ultimately, compliance engineering.

No military, intelligence agency, or major tech corporation invests in VR because of the art.

They invest because immersive media:

- shapes perception,

- increases emotional suggestibility,

- creates visceral memory,

- and trains behavioural responses faster than text or film.

When foreign-funded NGOs run youth “immersive storytelling labs,” they say:

“We are supporting African creative expression.”

But what they are also doing is:

- building a pipeline of African XR talent trained on foreign software ecosystems,

- orienting youth cultural production around donor-defined themes (climate, migration, gender, resilience, inclusion, tech for good, digital futures, mental health),

- seeding the future workforce for global immersive tech industries,

- grooming soft-power ambassadors aligned with donor norms,

- rehearsing values and narratives palatable to WEF and Western development agendas.

It is not “indoctrination” in the crude sense.

It is employment capture: shaping the skills, desires, and worldview of African youth so that they flow smoothly into globalized tech pipelines.

3. The Military–Industrial Shadow Behind Immersive Tech

This part is rarely spoken aloud in the arts sector: VR/AR is deeply entangled with defence, surveillance, policing, and military simulation.

Historically:

- The earliest large investments in VR came from the US military.

- Immersive training environments remain a key tool in defence strategy.

- The same companies that produce entertainment VR devices produce military simulation systems.

- Surveillance and AI companies rely on immersive modelling for urban mapping, drone operation, and anticipatory policing.

When African NGOs teach VR/AR under the banner of “climate storytelling” or “African futures,” they rarely mention that the same skills—3D modelling, environment mapping, motion capture, immersive UX—are directly transferable to military applications.

It is naïve to assume that the global enthusiasm for “XR in Africa” is merely aesthetic.

It is infrastructural.

4. The Move Toward “Post-Copyright Africa”: A New Frontier of Cultural Extraction

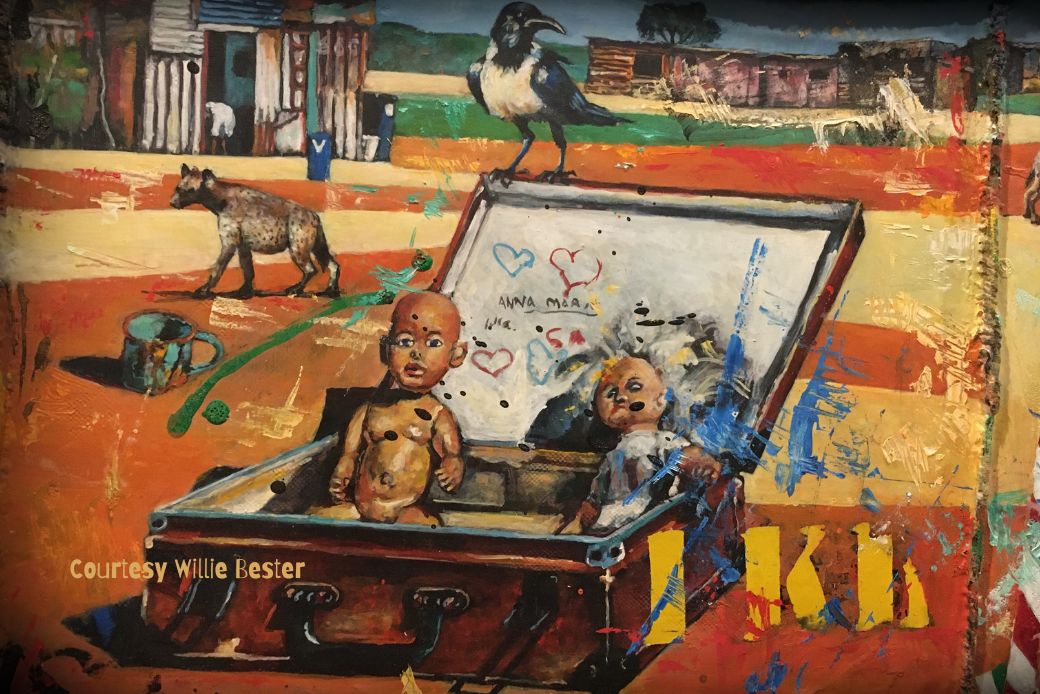

We now arrive at a more subtle operation: the rapid digitisation of African archives without adequate copyright clarity, cultural licensing, or community governance.

Foreign-funded digital heritage projects often claim:

“Copyright is too complex.”

“We are building an open commons.”

“We’re making African history accessible.”

But without:

- a national licensing framework,

- community-led custodianship,

- reciprocal benefit agreements,

- or African data sovereignty protections,

this “openness” becomes an open buffet for foreign institutions, universities, AI labs, and immersive media companies to:

- train generative AI models on African cultural material,

- use African imagery to produce Western-owned IP,

- build immersive experiences detached from local meaning,

- and rewrite colonial history through curated, sanitised, market-friendly lenses.

This is not accidental.

It is a new mode of cultural extraction—cleaner, digitised, harder to see.

5. South Africa as Test Site: Why Here? Why Now?

South Africa offers:

- world-class artists and creatives,

- sophisticated universities,

- affordable labour,

- a weakened cultural funding ecosystem,

- unstable public institutions,

- and a hunger for global recognition.

This creates the perfect opening for foreign NGOs to position themselves as saviours, innovators, patrons, futurists, while gently entering:

- our archives,

- our narratives,

- our creative labour,

- our technological future,

- and ultimately our imagination.

This is what extraction looks like in the 21st century: not violent, not overt—just soft, smiling, grant-funded, and beautifully branded.

6. We Need a New African Doctrine for Immersive Culture

The response is not to reject all foreign partnerships. It is to rewrite the terms of engagement.

South Africa needs:

- A National Immersive Media Charter regulating foreign influence.

- Community-driven archive governance and cultural licensing.

- Explicit data sovereignty protections for African cultural content.

- Funding models that keep African IP owned, controlled, and benefited locally.

- Strong domestic investment in African immersive tech—public, private, philanthropic.

- A new generation of African artists trained not just in VR, but in political literacy about VR.

If we do not act, we risk becoming the world’s cheap immersive content factory—a site of labour and imagination extraction that enriches everyone but us.

Africa’s cultural inheritance—its archives, myths, histories, and youth creativity—is not a raw material for global platforms.

It is our heritage, our wealth.

And it must stay ours.