AI, Ritual, and the Imaginal Commons from Singapore to South Africa

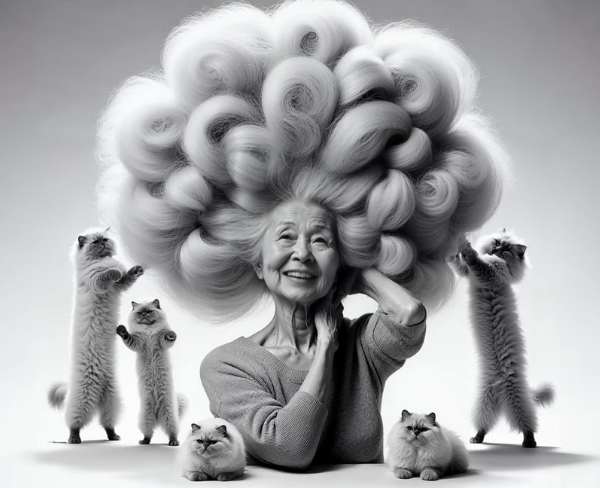

Digital art is often discussed in the language of technological progress using words like innovation, automation and acceleration. But a different conversation is taking place led by artists like Singapore’s Nice Aunties, whose practice positions digital art and AI not as a replacement for human imagination but as a rendering device for deeper interior images. Her work suggests that digital art can become a site for cultural repair, a domain where ancestral memory, collective ritual, and contemporary technologies meet in productive tension.

This article touches on how such practices resonate with the imaginal theories of Noel Cobb and Dennis Patrick Slattery, the dream-recording mythos of Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World, and South African indigenous philosophies, particularly Khoi and San traditions. Taken together, they offer a framework for reimagining emerging digital initiatives like Art Stoke Commons as aesthetic and pedagogical environments for collective re-sensing and cultural repair.

1. AI as Rendering, Not Imagination

Nice Aunties’ work resists the common narrative of AI as a machine that “thinks” or “creates.” Her digital scenes, often steeped in cultural texture, humour, and ritual gesture, foreground the human as the primary imaginer. AI serves as a prosthesis of interiority, a darkroom for dream-images and a translator of subtle, pre-verbal, archetypal material into shareable form.

This stance aligns closely with the theoretical lineage of the archetypal imagination, as developed by Noel Cobb. For Cobb, imagination is a subtle organ of perception, an interface between the personal psyche and the world-soul (the anima mundi). Technology can support this imaginal function only insofar as it does not supplant it. Cobb warned against “the death of imagination through simulation,” yet welcomed tools that help bring forth images that might otherwise remain unseen.

Dennis Patrick Slattery extends this thinking: imagination is not private fantasy but a cultural act. Art becomes a vessel for reassembling the shattered fragments—the shards—of lived experience, memory, and myth.

Nice Aunties’ practice fits precisely here: AI renders ancestral textures into digital form so they can be witnessed, played with, and felt anew.

2. Ritual as Technology of Cultural Repair

For both Cobb and Slattery, ritual is crucial. Ritual holds the imaginal in a container strong enough to move interior symbols into social life. It is a structure for remembering and re-membering—bringing back what has been forgotten or fragmented.

In Nice Aunties’ work, rituals appear everywhere: in the gathering of aunties, the exchange of food, the humorous exorcisms of daily life, the altars to cultural memory.

These are not nostalgic gestures. They perform what Slattery calls “mythopoetic coherence”, the act of stitching a torn cultural fabric through shared image and gesture.

This model echoes the iconic dream-device in Until the End of the World—a machine that records dreams not for entertainment, but as a means of healing the rupture between worlds, generations, and ways of knowing, perceiving and feeling. Dreams are not content; they are medicine.

Digital art, then, can be understood as ritualised witnessing: a process where communities gather around images that carry cultural density and emotional resonance.

3. South African Indigenous Imaginal Traditions: The Oldest Dream Technologies on Earth

To reimagine digital art as a space of cultural repair in South Africa, we need only look to the continent’s earliest image-makers: the Khoi and San. Their traditions offer philosophical, ethical, and aesthetic frameworks that profoundly align with Cobb–Slattery imaginal theory.

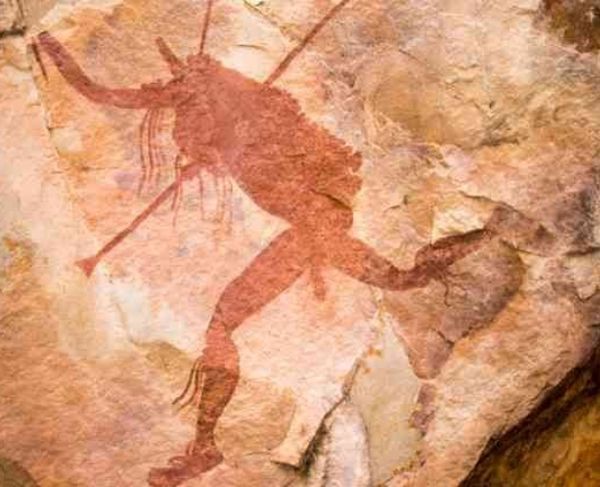

San Trance Imagery as a Dream-Recording Technology

San rock art is not representational painting—it is a technology of the imaginal:

- images carried back from trance states,

- visual repositories of healing knowledge,

- mediators between human and more-than-human worlds,

- aesthetic rituals performed for the health of the collective.

What Wenders imagined as future sci-fi—the dream recorder—has been present in Southern Africa for millennia.

The !kia Healing Dance as Communal Aesthetic Practice

The Khoi and San healing dance is a collective technology of transmutation. It works through:

- synchronised movement,

- rhythmic breath,

- collective energy (“!num”),

- an opening of the boundary between worlds.

Its purpose is relational repair. If someone in the community is suffering, it is not their illness—it is a disturbance in the entire relational field. This worldview can guide new digital practices toward communal ethics rather than extractive or individualistic ones.

The Ethics of Imaginal Responsibility

In these traditions, the imaginal is not entertainment but responsibility.

Images belong to the community; they must serve its balance and continuity.

This is precisely Cobb’s view: imagination must be in service to the anima mundi, not the ego.

4. Toward Art Stoke Commons: A New Digital Art Ecology

When you bring together the ideas of:

- Nice Aunties’ culturally rooted digital art and AI practice,

- Cobb’s archetypal imagination,

- Slattery’s narrative repair,

- the dream device of Until the End of the World, and

- the Khoi/San imaginal world,

a striking vision emerges for Art Stoke Commons.

Digital Art and AI as a “Dream Darkroom”

The platform becomes a space where individuals and communities develop dream-like, symbolic, or ancestral images—to render what is felt, sensed, or intuited (using AI as an optional technology).

Ritualised Creative Cycles

Instead of production pipelines, Art Stoke Commons becomes a place of ritualised creative cycles.

What would this look like?

- collective witnessing,

- communal rendering and interpretation of images,

- story circles,

- ethical protocols for ancestral knowledge.

This shifts the digital space from “content marketplace” to “creative hive”.

Ancestral Imaginal Philosophies as Compass

The Khoi and San offer methodologies—not motifs—for how digital images can be approached:

- as relational artifacts,

- as communal healing agents,

- as bridges between worlds,

- as containers for cultural density.

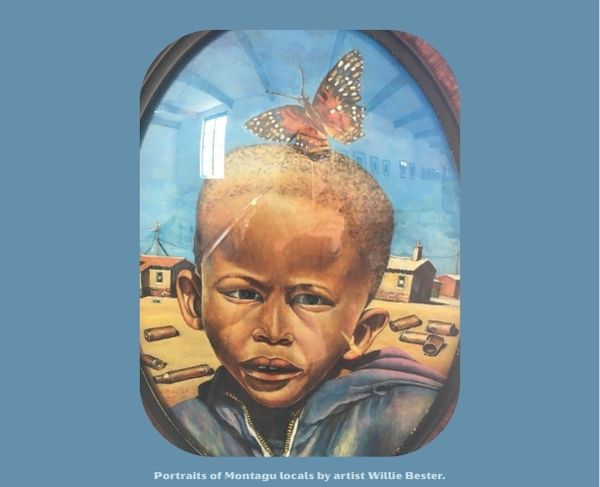

Cultural Repair as the Core Outcome

Art Stoke Commons becomes a site for what Slattery calls “living mythically”—where art does not escape the world but deepens our presence in it. Digital art, in this framework, is not about aesthetics alone. It is a social technology for feeling again, for repairing the imaginative numbness produced by colonialism, apartheid, capitalism, and digital acceleration.

Conclusion: The Future of Digital is Ancestral

Nice Aunties’ work hints at a future for digital art that is more human, more ritualised, and more ancestrally grounded. Cobb and Slattery provide the philosophical scaffolding; Khoi and San traditions offer the ethical and imaginal inheritance; dream technologies, fictional or real, show how images are medicine.

What emerges is a powerful proposition: digital art can become a contemporary dream cave—an imaginal commons for healing, memory, and cultural repair.

Art Stoke Commons has the potential to become such a space: not a gallery or marketplace, but a living ritual ecology where digital art and AI assists us in recalling what we have forgotten—our imaginative responsibility to one another, and to the worlds we inherit.