Why Are Billions Not Moving the Needle?

Year after year, philanthropic institutions pour billions into “impact” work – social justice, climate adaptation, education, food security. Yet the lived experience on the ground suggests something else: incremental wins, systemic stagnation, and a growing sense that the funding architecture itself is part of the problem.

We need to ask, why is so much money producing so little transformation?

The answer lies not in bad intentions but in bad design

- Top-down power structures that prioritize control over collaboration.

- Bureaucratic gatekeeping that filters out the most radical and relevant ideas.

- Funding cycles that reward visibility and metrics over long-term resilience.

- A complete lack of feedback from the communities most effected.

The way we fund is broken. And no amount of shiny RFPs or strategy resets will fix it until we redesign the fundamental architecture of trust, flow, and governance.

The Hidden Architecture of Traditional Philanthropy

Let’s take a closer look at how centralized funding models function.

- Control is centralized. Decision-making power lies with boards, selection panels, or donor executives.

- Narratives are curated. Applicants must shape their proposals to fit funders’ language, trends, or ideological preferences.

- Evaluation is extractive. Grantees are required to constantly prove their impact through donor-defined KPIs, often at the cost of doing the actual work.

- Risk is offloaded. Funders rarely bear the consequences of failure — grantees do.

- Learning is siloed. There’s little incentive to share what didn’t work, resulting in a repeating loop of short-term fixes.

This model doesn’t just hinder innovation — it actively suppresses it.

The Myth of Impact

We’ve inherited a definition of “impact” that is

- Quantifiable

- Easily visualized

- Short-term

- Scale-focused

But real change is often

- Emergent

- Messy and nonlinear

- Slow

- Deeply contextual

Funding for impact has become a performance: reports, dashboards, infographics — a theatre of change that rarely shifts the root conditions. The pursuit of scale often strips solutions of their nuance, their local relevance, and their cultural depth.

The result? An industry optimized for looking like it’s working — rather than actually working.

A New Paradigm: Decentralised Funding for Collective Intelligence

We’re not stuck because of a lack of money.

We’re stuck because we keep funding as if power is neutral.

To fund differently, we must begin with a different assumption: Those most affected by a problem are best positioned to design and resource its solution.

Decentralised funding challenges the monopoly of foundations, banks, and donors by redistributing not only money — but decision-making, governance, and accountability.

This doesn’t mean there’s no structure. On the contrary, it demands more intentional design, more trust architecture, and more digital literacy. But in return, it offers:

- Transparency. Every decision, every allocation, every transaction — visible and traceable.

- Participation. Community members become funders, voters, and stewards — not just recipients.

- Adaptability. Rules and priorities can evolve as conditions change, because the governance is built-in.

- Alignment. Incentives can be encoded to align with long-term social or ecological health — not donor optics.

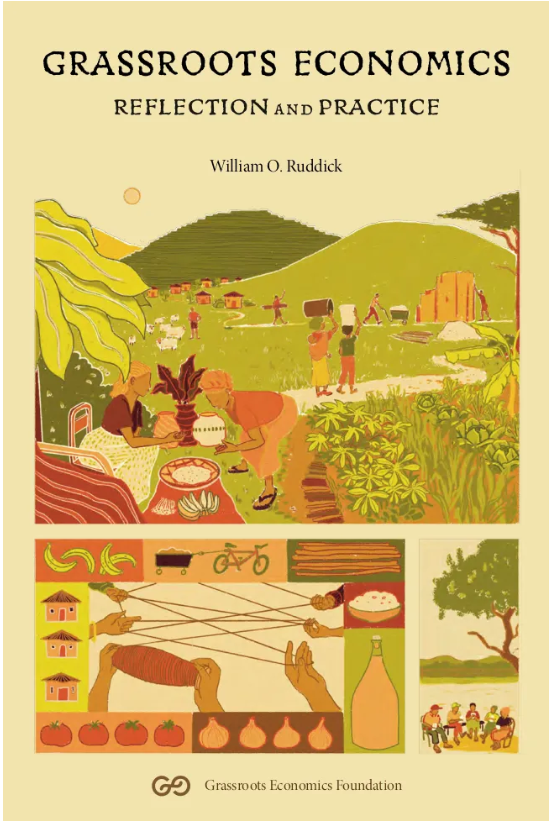

Case-in-Point: Grassroots Economics & the Power of Community Currencies

One of the most compelling examples of decentralized funding in action comes from Kenya’s Grassroots Economics, a social enterprise that has pioneered community currencies and blockchain-backed voucher economies.

In partnership with underserved communities, they’ve helped create localized financial systems that

- Circulate value internally, rather than leak it out.

- Reward community service, local trade, and social cooperation.

- Reduce dependency on external aid and donor cycles.

- Leverage blockchain tech for transparency and trust.

This isn’t theory. It’s operational, auditable, and has directly benefited thousands of people in informal settlements, rural regions, and refugee camps.

Why it matters

Instead of parachuting in solutions, Grassroots Economics builds the tools for self-organising economies. And because the ledger is open and the rules are shared, anyone can fork, adapt, or replicate the model for their context.

It’s not a silver bullet — but it’s a blueprint for something fundamentally different.

The Contrast: DGMT’s RFP and the Ongoing Struggle to Fund Differently

In March 2025, South Africa’s DGMT (the DG Murray Trust) released a Request for Proposals (RFP) to fund research that synthesizes best practices in collective impact programmes — aiming to understand what works, what doesn’t, and why.

The RFP deserves credit. It uses language that suggests openness to experimentation and a desire to do things differently. But here’s the tension: while the language of the RFP suggests evolution, the architecture of the call still rests on familiar pillars — structures that have long constrained real transformation:

- Funding is still controlled by a central committee.

- Decisions are made behind closed doors.

- Communities remain recipients — not co-designers.

- Scalability is still treated as the holy grail.

- The pool of “eligible” applicants is tightly defined — privileging established players over bold, emergent actors.

The last point cuts right to the heart of the systemic issue: who gets to be seen as credible, fundable, or capable of producing “impact” — and how those gatekeeping mechanisms reinforce the very hierarchies and limitations the RFP claims to challenge.

Funders and governments alike demand evidence that projects are “scalable” — but rarely interrogate what that actually means. Is the goal to replicate a single model across contexts? Or to seed diverse, context-specific solutions that share common principles?

This is where decentralised funding frameworks offer an essential pivot. Unlike rigid vertical pipelines, decentralised approaches value coordination over control. They embrace complexity and emergent design. They recognise that the knowledge to solve systemic issues does not sit with any one organisation — but in the network itself.

The work of Grassroots Economics here is instructive. Their use of blockchain to facilitate community inclusion currencies has empowered local networks to develop their own economic safety nets — outside of top-down donor dependency. This is collective impact, not as a theory, but as a lived, decentralised infrastructure that adapts to the specific needs of each community.

What DGMT’s RFP reveals — even if unintentionally — is a shift already underway: the call for new funding arrangements, new structures of operation, and new understandings of collective power. But to truly walk that path, we must challenge the myth that our current philanthropic models are built to generate impact. They are not. They are built to manage and preserve power.

A Call to Action: Funding Systems, Not Symptoms

It’s time to fund like we mean it.

That means funding not for scale, but for stewardship. Not for outputs, but for ecosystem resilience. Not for glossy outcomes, but for messy, iterative processes that build new worlds from the inside out.

When funders like DGMT continue to centre scalability — even while inviting innovation — they inadvertently signal a desire for centralized control over community-led adaptation. But scale is not always the goal in complex systems. Sometimes what’s needed is replication, variation, slowness, and depth.

If we want real change, we must rewire not just how we spend money, but how we trust.

Here’s what that requires

- Fund the ecosystem, not the siloed initiative.

- Design for local governance, not global branding.

- Support infrastructural literacy — including tools like DAOs, community currencies, and mutual credit systems.

- Experiment publicly, learn in the open, and share what doesn’t work.

- Value cultural and relational capital just as much as financial returns.

In Short

We need funders who are willing to become facilitators of coordination, not custodians of capital.

We need frameworks like Grassroots Economics, where community value is created and circulated from within — and we need hundreds of such experiments, adapted to place, culture, and context.

Because the way we fund is broken.

But the future is not.

It is emergent. It is already here.

We just need to fund it differently.

Glossary of Terms

- DAO (Decentralized Autonomous Organization): A digital organization governed by rules encoded in smart contracts, enabling transparent, community-based decision-making.

- Community Currency: A locally-created and circulated currency designed to boost internal trade and resilience.

- Commons-based funding: Models where shared resources are governed collectively, often without reliance on external funders.

- Scalability vs. Replicability: Scalability aims to grow a single solution big; replicability supports diverse, localized solutions to spread organically.